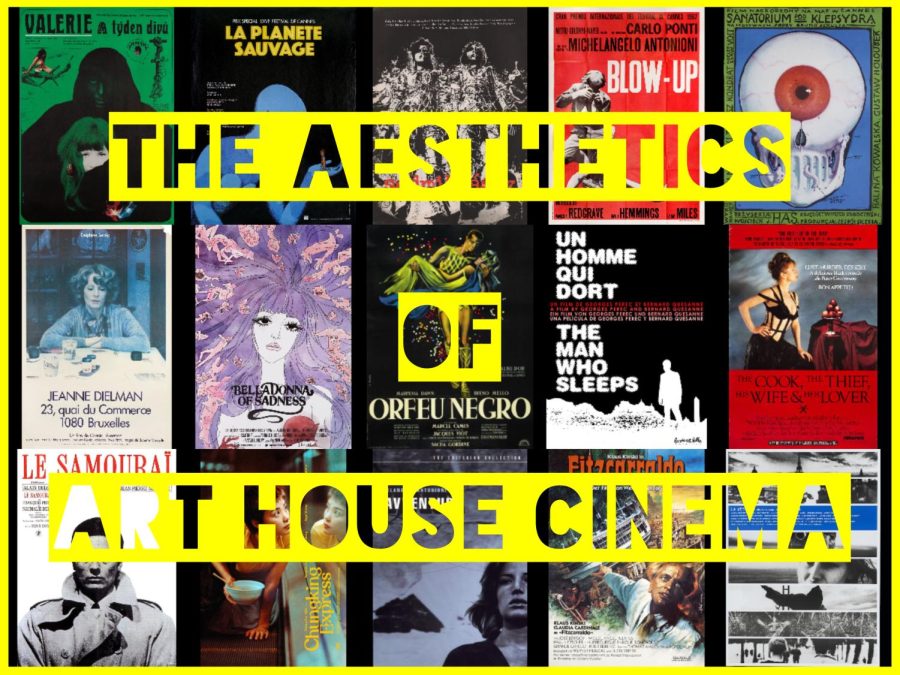

The Aesthetics of Art House Films: What Sets Them Apart? – Part 2

March 13, 2023

Having delved into the history of art house cinema and the defining characteristics of such films in the first part, it is worth noting that as the film industry has evolved, so has the boundary between art house and mainstream become increasingly blurred. With many films now crossing over into both categories, it can be challenging to distinguish clearly between the two. In this regard, it is important to examine some notable examples of films that occupy this liminal space and explore what makes them unique. From experimental works by established auteurs to genre-bending blockbusters, these films challenge conventional categorizations and offer exciting new possibilities for cinema.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” is a 2014 film directed by Wes Anderson, with a screenplay written based on Stefan Zweig’s writings. The film is set amid World Wars I and II in the fictitious European Republic of Zubrowka and chronicles the exploits of Gustave H., the renowned concierge of the titular hotel, and his young protégé, Zero Moustafa.

The film’s detailed set design is key to its visual style, with every aspect of the hotel meticulously crafted to create an immersive and fantastic world and induce a sense of nostalgia. The attention to detail in the set design, including the use of miniatures and hand-painted backdrops, creates a dreamlike vibe that adds to the film’s art-house feel. One of the most striking aspects of the film’s visual style is its use of color. The color palette is rich and vibrant, with a mix of pastels and bright hues contributing to the atmosphere. Color serves as one of the most defining qualities of the film’s visual style. The film frequently employs symmetrical framing, with actors centered in the frame and surrounded by a flawlessly balanced composition of objects and architecture. This results in visual harmony and balance that is attractive to the eye and evocative of traditional art and design. Another visual feature of this film is how the aspect ratios shift throughout the film based on the current period. The film begins in the modern day and is presented in widescreen format with a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, then switches to a 2:40:1 ratio for the scenes taking place in 1968, and finally 1.37:1 format for the scenes set in 1932. The different aspect ratios in turn help create a visually engaging experience for the viewer.

The film’s narrative structure is non-linear and delicately embedded. In the first few moments, we witness a young girl reading a book by a famous author, who recounts his 1968 vacation at the once-grand, then-drab hotel after its transition to modernist-communist aesthetics. There, he meets its owner, Zero Moustafa, who at dinner tells how he came to acquire the hotel. The connection between Monsieur Gustave, the concierge of the Grand Budapest Hotel, and his trusty employee, Zero Moustafa, is at the heart of the story. Gustave is a larger-than-life character with total control over his life; he is also a bit of a gigolo who keeps his relations with many of the hotel’s elderly, affluent, unmarried, and blonde female visitors private. Gustave often recites poetry and maintains decorum, yet also occasionally slips into vulgarity. While the film is mostly set in 1932, it shifts back and forth in time, emphasizing the ephemeral nature of time, history, and stories. While the film is humorous, it also has a melancholic tone, which is accentuated by the historical perspective, with the director depicting the inevitability of degradation. The film also shows the fading importance of the wealthy class and changes in the social and political landscape of Europe. The film’s cameos, cinematography, and mise en scène are impeccably controlled, with the aspect ratio and palette changing to reflect different time periods. Zubrowka, the fictional setting between the two world wars, is a mishmash of Central, Alpine, and Eastern Europe, presenting a tension between “civilization” and “savagery.” The rise of Fascism and Communism is referenced, adding complexity to the film’s layered narrative. Anderson’s controlled tone heightens the influence of brutality and vulgarity, reminding us that aesthetics cannot always shield us from evil.

The film uses sound design appropriately, particularly where Zero and Gustave visit a church in the mountains to find who betrayed them. A non-diegetic score is present throughout the sequence, but at certain points, it is replaced with diegetic sounds to emphasize the location’s isolation and establish atmosphere. The score grows more complex as the plot does, and diegetic sound effects are used to attract attention to character actions. For instance, there is a gas pump sound effect when the shot focuses on a mechanic next to a petrol pump, and footsteps get louder as a character approaches. The score also changes to have a more chanting effect when Zero and Gustave enter the church wearing white robes. Additionally, the sound design in the prison scenes is used to highlight the film’s dark humor. The scene where the prisoners plan their escape is a fitting example. The sound of the tools they use to dig their tunnel is exaggerated, creating a comical effect. This sound design choice adds levity to the scene and is a hallmark of the film’s overall style.

Lost in Translation

“Lost in Translation” is a 2003 romantic comedy-drama film written and directed by Sofia Coppola. The plot centers around Bob Harris, an aging Hollywood actor who travels to Tokyo to shoot a whiskey commercial. He feels isolated and disconnected from his surroundings in a new city. He meets Charlotte, a young college graduate who is also staying with her husband at the same hotel. They form an unlikely relationship as they both confront their own personal struggles and spend their nights exploring the city together.

This film embraces a minimalist approach to cinematography, reflected in its sparse use of artificial lighting, frequent use of handheld cameras in many scenes, and attention to minute details and subtle moments. The themes present in this film are visualized in part by a palette of muted cool tones. Slate blues and grays are staples throughout the beginning of the film. The palette eventually switches into a slightly warmer tone in the scene where the two lead characters, Bob and Charlotte, meet in a quiet and dimly lit bar in a Tokyo hotel with a sullen ambiance that mirrors the two characters’ emotional state. Blue and red lights flicker over the metropolitan skyline in the background. The lighting is soft and low, casting shadows on the walls and enticing the audience into their dialogue. Close-up shots and shallow focus draw attention to the characters’ expressions and body language. In a later scene following a train ride, the ordinarily vivid and verdant grounds of the Nanzen-ji Temple and Heian Jingu shrine are muted by a gloomy overcast sky which follows Charlotte when she visits Kyoto. The wide shot of her standing beneath a colossal Sanmon entrance gate towering over the treetops is tempered by earth tones and mellow lighting, evoking an ethereal quality that accentuates her feelings of dissociation from her surroundings.

“Lost in Translation” prioritizes the progression of Bob and Charlotte’s relationship over the plot. The film is structured around a series of loosely connected stories that capture the mood and atmosphere of Tokyo and the characters’ evolving feelings. Tokyo is presented as a city of excess that offers a hollow promise of contentment, with the two main characters sharing a sense of emptiness as they search for meaning in Tokyo’s attractions. In the 36-second opening shot, we see Charlotte’s backside as she rests on a bed whilst wearing translucent pink underwear typical of John Kacere’s photorealistic paintings, whose paintings are shown in the hotel later. There are several interpretations of this scene; some argue that the filmmaker intended for the scene to contravene taboos and subvert preconceptions around what may be considered the money shot in more standard exploitive cinema; others argue that the shot persists for so long that it becomes awkward, forcing the audience to become aware of, and even question, their participation in the gaze. Additionally, the film defies several popular romance film conventions in preference for a more postmodern portrayal of love. Most notably, Coppola’s decision not to unite the two characters, Bob and Charlotte, in the end. Multiple reasons contribute to this ambiguity, including the difference in age between a middle-aged man and a young woman; the absence of physical intimacy, which makes it unclear if their relationship is romantic or platonic; and the open-ended conclusion, which leaves the fate of the main characters’ relationship unresolved, leaving the audience to interpret the final scene in which they part ways.

The film’s soundtrack features songs from the shoegaze and dream pop genres, both of which have a meditative, mystical vibe. Kevin Shields and other artists created several unique tracks to evoke a melancholic and nostalgic aura, along with a sort of forlorn sound that conjures feelings of isolation and uncertainty. The soundtrack, paired with the existing ambience in the setting, such as the city traffic, a self-help audio recording, or even the grating sound of a fax machine which immerses the audience in the film’s environment. The soundtrack of the film also uses music to reflect the characters’ emotional states. For example, after being chased out of a bar, dashing through a pachinko parlor, and snapping polaroids while dancing with stoners, the group heads to a karaoke bar. The lyrics of the songs sung at the karaoke bar by Bob and Charlotte, “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love, and Understanding” by Elvis Costello and the Attractions, “Brass in Pocket” by The Pretenders, and “More Than This” by Roxy Music, provide subtext about the protagonists’ personal lives and their relationship. The latter, “More Than This,” is directed at Charlotte as Bob periodically glances over in her direction. It is a song that recounts a broken love affair, and certain things don’t last forever, alluding to the main protagonists eventually splitting up. Similarly, Air’s ambient piece “Alone in Kyoto” serves as background music for Charlotte’s trip to Kyoto, which is her attempt, like many tourists, to discover spiritual enlightenment, only to find nothing to fill what is missing.

Amélie

“Amélie,” also known as “Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain,” is a 2001 French romantic comedy film directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and co-written by Jeunet and Guillaume Laurant that ranks among my personal favorites. The film tells the story of Amelie, a young woman who lives a solitary life in Paris. To cope with her loneliness, she develops an active imagination and a mischievous personality. Amelie embarks out on a mission to help others find happiness and love after discovering an old box of childhood keepsakes hidden in her apartment. Amélie affects the everyday lives of others around her through a series of odd and humorous incidents, including a reclusive painter, a hypochondriac, and a man who collects discarded photographs from passport photo booths. Amélie explores the possibilities of love as she learns to open herself up to the world.

In order to tell its story and illustrate its themes, “Amélie” employs an array of aesthetic qualities including color, cinematography, and composition. Its distinctive color palette and overall green hue is among “Amélie’s” most striking aesthetic features. Throughout the film, Jeunet combines yellow, green, and red tones to depict warmth, passion, and energy. The yellow and greenish tones generate warmth, compassion, and romanticism, letting viewers feel at ease while watching the film. Red is heavily featured in the opening scene and is associated with Amélie’s childhood memories, such as her father’s garden gnome wearing a red cap and the various shades of red within her apartment. The colors used also go hand in hand with Amélie’s personality. As characters’ memories are being shown, they are in black and white, presenting a historical context for viewers to connect with earlier films that were unable to render color. Amélie also employs a variety of camera shots to convey different meanings. The use of camera panning establishes the environment for viewers to understand what is going on around the characters, particularly Amélie. Moreover, the use of close-ups is a defining aspect of the film, highlighting the meticulous process of experimenting with different lenses that accentuate each character’s physical characteristics prior to filming close-ups while also creating a distorted effect that fits Jeunet’s comedic style. Also, the use of wide shots provides stunning visuals of the surrounding scenery and characters, allowing the audience to take it all in. The scene showing Amélie on a bridge skipping stones across the water is a fitting example. Zoom techniques are also used to create an emotional connection and familiarity with the audience, allowing them to recognize the characters’ feelings. The out-of-focus background brings more attention to the character’s visage, highlighting their expressions. In fast-paced scenes, the camera is raced up to characters to depict abrupt shifts in mood, and the dolly shot is utilized to introduce characters into the narrative. In addition, motion is used to emphasize Amélie’s effervescent disposition. If she is elated or cheerful, swift motion is used; when she is unhappy or frightened, a more sluggish motion is used. This method efficiently communicates the character’s state of mind to the viewer, allowing them to thoroughly empathize with her circumstances. Framing is another essential aspect of the film, with the character set in the center of the shot, whether far away or close to the camera lens, with over-the-shoulder shots being the exception. Scenes with Amélie in her kitchen are framed by an open window, creating an elegant shot of the character in her own environment.

The premise of the film offers a fresh, quirky twist on a formula that has proven reliable for many other movies. The plot begins on August 31st, 1997, coinciding with the death of Princess Diana due to injuries sustained in a car accident in Paris, France. Were told that Amélie’s mother was killed after a suicidal Canadian tourist leapt from the roof of Notre-Dame de Paris and crashed on her when she was six years old. Which is why, as he ages, her father becomes increasingly reclusive. At the age of 18, she eventually leaves home to work as a waitress at Montmartre’s Café des 2 Moulins, wherein she relishes in simple pleasures like digging her fingers into sacks of grain or breaking crème brûlée with a spoon. The film’s focus on Amelie’s perspective prompts it to neglect its narrative to deliver a convincing depiction of her worldview. The fundamental message of the film is to maintain optimism and humor in the most adverse situations, and it encourages viewers to always search for the good in others. The film emphasizes that anyone who helps others will eventually receive help in return. Additionally, the inclusion of a narrator who does not contribute directly to the story is one of the film’s more intriguing approaches. Narrators are typically used to outline a film and provide information that cannot be presented otherwise. Yet, the narrator’s omniscience is exploited in Amélie, as he regularly arrives out of nowhere to brazenly disclose the characters’ pasts. Even though most of this information is delivered through the storyline, he takes control of the narrative for a second to underline the intentions and emotions of the characters. The presence of the narrator enriches the movie’s charm and distinctiveness despite this departure from the conventional “show, don’t tell” rule of film. Amélie’s imagination and thought processes are projected through the narrator, who elevates the mundane to the extraordinary and makes ordinary situations appear grandiose. The result is a remarkable masterpiece, and Amelie’s character exemplifies the power of a driven imagination which can find pleasure in the most insignificant things.

When used to emphasize finer details, such as our understanding of the characters’ tastes and idiosyncrasies, the film’s sound design is at its best. Every little sound is distinct and serves to emphasize the delight and excitement of discovery. The more important the moments being portrayed on screen are to the characters, the more detail seems to have been put into the sound. Early in the film, there is a surreal scene inside a metro station, where Amélie hears a distant old record playing. It echoes hauntingly down the green-tinted underground tunnels, sounding increasingly like a ghost as she comes closer. The mystery is cleared when it is revealed that the music is emanating from an old gramophone resting on the lap of an elderly blind man. It is never apparent if there is a deeper rationale for his whereabouts and actions. Yet, the viewer is given everything they need to know about the film in a scene devoid of any conversation or narration. This film embraces life’s peculiarities and the notion that not everything deserves or even merits an explanation. It is a film about nostalgia, recollection, and love. Correspondingly, Yann Tiersen’s score elevates the atmosphere and keeps reality at bay, enabling the music to whisk the viewer away inside the film’s universe whilst also stepping back to unveil how a trivial sound accent complements the film’s most delicate and curious moments. One memorable scene is when Amélie sends Mr. Bretodeau the box of mementos anonymously, leaving him thrilled. Amélie dances in the street and assists an elderly blind man in crossing the street. The music “La Noyée” starts playing as the scene unfolds and becomes more vivid, intensifying the emotion of the moment. The song’s synchronization with the start of Amélie’s colorful description of the street further enhances the overall effect of the scene.

Black Swan

“Black Swan” is Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 psychological horror film, with a script written by Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz, and John McLaughlin. The story follows Nina, a brilliant ballerina who is cast as the lead in a forthcoming Swan Lake production. The strain and competitiveness within the ballet group begin to take a toll on Nina’s mental health as she strives for excellence in her performance. She begins to hallucinate and suffers from delusions that blur the barrier between reality and fantasy as she grows increasingly obsessed with executing the role of the Black Swan.

The juxtaposition of macabre elements with depictions of mental illness in “Black Swan” creates a striking and unsettling commentary on the nature of obsession and creative ambition. The way Aronofsky portrays the visuals in “Black Swan” is incredibly significant in articulating the film’s representation of psychosis. Nina, the main character, is portrayed to be mentally unstable, and the film creates an unnerving atmosphere that echoes Nina’s internal turmoil using various camera techniques and a self-reflective style. Movement is important in “Black Swan”, which complemented Aronofsky’s last film, “The Wrestler.” Nina’s thoughts are shown in movement, as she strives for perfection and seldom stays still. Even when she is not constantly moving, the camera follows her everywhere. This results in a psychotic state that plagues her every action and perception of her surroundings. The use of cinema vérité, a documentary filmmaking approach that captures the actuality of an individual, a moment, or an event without any rearrangement for the camera, gives viewers an understanding of reality within “Black Swan’s” harrowing setting. This film is a mix of fictitious works, including Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake ballet, Dostoyevsky’s short tale “The Double,” and Satoshi Kon’s anime thriller Perfect Blue. Because of Nina’s desire for perfection, her actions are a performance, and the lack of control communicated by the camera’s movements reinforces this truth. The film has doubles and mirrors, adding to the central protagonist, Nina’s, sense of paranoia. Nina’s counterpart, Lily, is everything Nina strives to be yet loathes, which ignites an attraction that escalates into an obsession. Cinematography plays with this idea by providing episodes of thwarted meta-reflexivity whereby the camera should be staring at itself but instead shows something else. Because one actress performs both roles: the White Swan and the Black Swan, the doubles are critical to deciphering the performance. Nina, the Swan Queen, must be both, but the duplicates drive her insane. The film uses oscillation between Portman and Kunis’ facets to create a hybrid creature. Both actresses’ appearances contrast significantly, with Portman having a delicate and heavenly face and Kunis having sharper features that insinuate eroticism and treachery. Mirrors serve a purpose in the film to reflect the ego and give insight into the narrow threshold between self and perception of the other. The physical stage set is a mirror reflection of Nina’s psychological condition. The entrance of the ebullient and fervent Black Swan, Odile, and Nina’s return to the ballet narrative are marked by the opening of tall, glittering gates on a black stage. Odile’s appearance becomes much more intense as Nina comes closer to the stage’s forefront, indicating Nina’s psychological metamorphosis. As the sequence and scene wrap up, Nina steps off the stage and into her dressing room, her expression becoming much more fearful and helpless, signaling the eventual waning of her destructive nature. This indicates that the stage is integral to her expression of Odile, a form in which Nina can shed her fears and inhibitions. Which is why her physical surroundings are essential for the understanding of her psyche and hence, the transformative process she undergoes.

Apart from Aronofsky’s preceding works, “Black Swan” is delivered chronologically. He took the classic ballet melodrama and brilliantly reimagined it on a cinematic scale. “Black Swan” partially resembles the motifs of the ballet “Swan Lake” alongside a magnificent soundtrack. The lead character’s plunge into insanity culminates in both the ballet and the film’s dramatic crescendo. The film begins with Nina’s dream about the prologue of Swan Lake, in which the sorcerer Rothbart casts his spell on Princess Odette. This serves a variety of purposes: it sets a Kafkaesque tone for the film, it connects the film’s narrative with the ballet’s storyline, and it signals that Nina herself has fallen into a trance. In the following scene, Nina is seen riding on the subway where she sees her reflection in a window of the subway, and her mirrored face is deliberately unclear as her alternate persona has not yet fully emerged. The motif of reflection and duality is important in exploring Nina’s character throughout the film. In certain respects, the film can be analyzed using psychoanalytic concepts involving the id, ego, and superego, as well as repression. As the white swan, she represents purity, innocence, and grace, which aligns with her superego. Yet, as the black swan, she represents eroticism, wickedness, and defiance, all of which correspond to her id. The arrival of the Black Swan from the mirror denotes Nina’s liberation as she has been repressed throughout her entire life due to her strict upbringing and perfectionism. Because of her innocent and childish manner, she finds it difficult to embrace her darker impulses. Her interactions with Lily are a turning point, as they symbolize a teenage-like rebellion against her mother’s authority. Nina has a significant breakthrough when she finally locks her mother out and openly accepts her sexuality. And during the film, signs of Nina’s severe psychological condition gradually emerge. Nina’s deterioration is due to her controlling mother; however, it is ambiguous whether the mother’s fixation or Nina’s mental illness arose beforehand. Also, her harmful, compulsive skin picking is a sign of Dermatillomania, a real life impulse. But the film does not solely focus on a mentally ill girl on the precipice of insanity, but it also raises a deeper point about the profession and its trappings. Other hallucinations, such as the apparition of feathers and wings, represent Nina’s fears of losing herself and becoming consumed by her role as the Black Swan. The feathers also symbolize her metamorphosis and the demise of her former self. In another scene, Nina is surprised to see Lily clothed as the black swan at her vanity upon returning to her dressing room in a distressed condition after her performance as the white swan. Lily begins to tease Nina for not being ready for the role of the black swan, and then morphs into Nina’s black swan doppelganger. This results in a violent struggle between Nina and her double, leading to Nina stabbing and killing who she assumes is her malevolent doppelganger but turns out to be Lily. This scene effectively demonstrates the concept of duality by demonstrating the muddled distinction between one’s true self and how others perceive them. These hallucinations contribute to the plot by stressing Nina’s mental burden and the hardship she undergoes in her role as the lead. Also, they serve to generate tension and suspense, alluding to the film’s grim conclusion. Nina’s hallucinations are less important than the fact that she is a professional ballet dancer who only settles for excellence. As shown in a few instances, the stress that ballet dancers endure to uphold rigorous criteria can be both mentally and physically debilitating, and it can even result in suicide. Nina’s pursuit for perfection leads to her nearly eviscerating herself after executing her masterpiece flawlessly in the end. Nina is pleased with herself, despite the tragedy of her actions, proving her idea of flawless was excessive.

Though some art house films have found success with mainstream audiences, plenty of others remain strongly rooted in the art house category. In the following section, we will look at several entry-level and niche art house films and what differentiates them from their more mainstream equivalents.

Fitzcarraldo

Werner Herzog’s 1982 film “Fitzcarraldo” stars Klaus Kinski as Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, also known as Fitzcarraldo. The film follows Fitzcarraldo, an ambitious and eccentric Irishman living in Peru who is obsessed with constructing an opera theater in the middle of the jungle. Fitzcarraldo intends to utilize a vast region of rubber trees to finance his dream, but to do so, he must transport a steamship over a steep hill to reach the untapped resources on the other side. Fitzcarraldo’s increasingly desperate attempts at accomplishing his objective result in clashes with the villagers, poor working conditions, and a final climactic effort to haul the ship over the hill. Fitzcarraldo is supported along the way by a native woman named Molly and a dedicated crew of laborers, but he is also contested by a rival rubber baron named Don Aquilino. The superb cinematography in “Fitzcarraldo” conveys the majesty and grandeur of the Amazon jungle, as well as the portrayal of a man driven to accomplish an inconceivable dream at any cost. The film also examines imperialism, cultural problems, and ecological exploitation of resources.

Blow-Up

“Blow-Up” is a 1966 film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni. This film is a mystery thriller that explores the topics of truth, perception, and meaning in contemporary society. The plot revolves around Thomas, a fashion photographer in Swinging London who becomes enamored with a series of images he snapped in a park. He becomes convinced that he has captured proof of a murder as he analyses the photographs. A skilled cast makes up the film, including Sarah Miles as Patricia, Vanessa Redgrave as Jane, and David Hemmings as Thomas. The soundtrack features tracks by jazz legend Herbie Hancock along with some of the era’s most iconic songs. ” Blow-Up” is a visually striking film, with Antonioni’s trademark long shots and minimalistic compositions providing a feeling of seclusion and desolation. The film assesses modern life’s dullness and superficiality, and the collapse of traditional moral values in the postwar age. “Blow-Up” is an engaging and aesthetically spectacular film that dives into the intricacies of reality and perception in everyday society. It is regarded as a masterpiece of 1960s film and a defining moment in Michelangelo Antonioni’s career.

Innocence

“Innocence” is a French drama film directed by Lucile Hadzihalilovic that was released in 2004. The film is a disturbing and eerie investigation of a secret boarding school for young girls where bizarre rituals and activities happen. The plot centers on Iris, a new student who enrolls at the institute and therefore is quickly sucked into the mysterious world that exists within. She creates good ties with two other students, Bianca and Alice, who share her interest in the school’s secrets. As the film progresses, it becomes clearer that there is something nefarious going on at the institution. Strange medical operations and hypnotic sessions are performed on the girls, and they begin to have weird hallucinations and nightmares. The school’s administration and teachers are extremely enigmatic, and all appear to be keeping the girls in a twisted world of their own making. “Innocence” has magnificent visuals and an achingly exquisite sound. The film’s nightmarish nature contributes to the overall aura of secrecy and fear. The young actresses bring innocence and vulnerability to their roles that cause viewers to care about their fate.

Love Exposure

“Love Exposure” is a 2008 Japanese film directed by Sion Sono. The film is a grandiose, epic tale about religion, sexual awakening, and love. It chronicles the experience of Yu, a teenager whose father is a Catholic priest. Yu’s father becomes obsessed with sin after his mother dies and begins to pressure his son to confess to sins he has not committed. Yu begins to commit crimes deliberately to satisfy his father, and eventually becomes a competent upskirt photographer. Yu meets his Virgin Mary, a girl named Yoko, while out taking pictures one day. Yoko is similarly suffering with her own sexual desires. They become romantically involved, but Yoko is the daughter of a cult leader he is aiming to infiltrate, and her father is determined to safeguard her from Yu. They must overcome a slew of challenges, including a spiteful ex-girlfriend, a gang of street fighters, and Yoko’s increasingly volatile father. The film is a chaotic, unique experience that digs into many topics such as religion, sexuality, gender roles, and societal expectations. The film is known for its lengthy running time (about four hours), spectacular visuals, and unabashed treatment of forbidden subject matter. Despite its contentious nature, “Love Exposure” has gained a cult following and is often recognized as one of the finest films of the 2000s.

Daisies

“Daisies” is a 1966 Czechoslovakian film directed by Vera Chytilova. The film follows two young women both named Marie as they rebel against societal norms and expectations. The film is typically identified with the Czech New Wave movement, defined by form and stylistic experimentation and openness to challenging political and social customs. The incorporation of brilliant, bold colors and lively, surreal images in “Daisies” seeks to emphasize the film’s central themes of youthful exuberance and disdain of societal restraints. The two Maries are portrayed as mischievous and boisterous, delighted in disregarding rules and wreaking havoc everywhere they go. During the film, the two women engage in absurdist and anarchic activities such as gorging on mounds of food in a restaurant and cutting up phallic objects with scissors. They also engage in philosophical disputes regarding the meaning of existence and morality, occasionally arriving at irreverent and contradictory conclusions. At times, “Daisies” could be viewed as a critique on the changes in politics and society of the 1960s, since the film’s mocking tone can be regarded as a response towards Soviet-era Czechoslovakia’s stringent conformity. Nonetheless, the film’s whimsical, non-linear structure and absence of a coherent storyline make pinpointing a specific message or message tricky.

Chungking Express

Chungking Express is a 1994 film directed by Wong Kar-wai. The film is a romantic comedy-drama mostly about the lives of two police officers who are struggling with the fallout from failed romances. The movie takes place in Hong Kong and covers themes such as loneliness, intimacy, and the ephemerality of existence. The film is broken into two portions, and each one focuses on a separate police officer. Officer 223 is dealing with the end of his relationship with his fiancée in the first segment. He begins to visit a fast-food establishment, where he befriends the owner, Faye. The second act follows Officer 663, who is also going through a breakup. He meets Brigitte Lin, a lady with a blonde wig who is involved in the drug trade. They start dating, but she soon vanishes, leaving Officer 663 to search for her. The film is acclaimed for its cinematography and distinctive narrative structure. It explores its characters’ emotions in a nonlinear and imaginative manner, combining fragmented narration and repetition to depict the characters’ sense of dislocation and uncertainty. Chungking Express has been acclaimed for its naturalistic characters, the creative narrative approach, and knack for capturing the atmosphere and spirit of Hong Kong. It is now considered a timeless classic and one of the best films of the 1990s.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is a 1970 Czechoslovakian surrealist film directed by Jaromil Jireš. The film is based on the novel of the same name by Vítězslav Nezval, and it tells the story of a girl named Valerie who experiences a surreal and magical coming-of-age journey. The story is set in a little village in a Gothic fairytale atmosphere. Valerie is an innocent girl who discovers she is the result of her mother’s illicit love affair with a vampire-like apparition. Valerie’s grandmother, who is also a vampire, takes her under her wing and guides her through a series of strange and disturbing events. As Valerie navigates through her strange journey, she encounters a cast of unusual characters, including a priest who may be a vampire, a group of bird-like creatures who kidnap her, and a beautiful young man who she falls in love with. Valerie encounters a peculiar array of individuals throughout her strange odyssey, including a priest who may be a vampire, a flock of bird-like creatures who abduct her, and a young man with whom she falls in love. Valerie confronts her own sexuality and female identity during her adventure. The film is recognized for its beautiful and mystical visuals, dense symbolism, and examination of subjects such as sexuality, the supernatural, and the loss of innocence. The film’s unique gauzy visual styles and evocative music enhance its ethereal atmosphere. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is recognized as a Czech cinematic gem, commended for its avant-garde aesthetic and poetic storyline.

The Hourglass Sanatorium

“The Hourglass Sanatorium” is a 1973 surrealist film directed by Polish film director Wojciech Has, based on a collection of short stories by the Jewish writer Bruno Schulz. The story follows Józef, a man who visits his father in a strange sanatorium, where time is suspended and dreams and reality blend together. Józef wanders through the strange and fantastical world of the sanatorium, encountering a variety of characters who challenge his perceptions of reality and memory. The Hourglass Sanatorium” is a complex and layered film that blends surrealism, phantasmagoria, and historical allegory. It explores themes of memory, identity, and the passage of time, as well as the trauma and disorientation of the Holocaust and the Nazi occupation of Poland.

The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover

“The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover,” directed by Peter Greenaway, is a critically acclaimed British film. The 1989 film is a bleak and macabre satire that delves into issues of power, love, and betrayal. The plot revolves around Albert Spica, a despotic and cruel gangster who runs a high-end French restaurant. Spica is accompanied by his long-suffering wife Georgina, who withstands his constant humiliation and abuse. Georgina finds solace in an affair with a bookish patron of the restaurant named Michael. The two lovers continue their tryst in private, hidden away in the restaurant’s storage rooms and bathrooms. As the affair unfolds, tensions between Spica and his cronies intensify, leading to violent clashes and power struggles. The opulent and grotesque visual style of the film is noteworthy, with sumptuous set design and a highly stylized color palette.

In a world where the dominant cultural narratives are often simplistic and shallow, art films offer a much-needed alternative. They challenge us to think critically and engage with complex ideas and can enrich our understanding of the world around us. Therefore, watching art house films is an important and valuable endeavor for anyone who wants to broaden their horizons and deepen their appreciation for the art of cinema.